(Trigger Warning: Discussion of violent crime, including details)

According to Edison Research, True Crime podcasts are, by far, the most likely to succeed, with a whopping 3.8% of shows placing in the Top 200. To put that number in perspective, it is more than four times the success rate of another leading genre, business (0.9%), and it towers over categories like health (0.5%) and education (0.2%). True Crime also thrives in other mediums, being the sixth most-watched movie genre on Netflix and the inspiration behind many novels.

It is easy to see this as a net positive. After all, bringing attention to these cases gives the families justice… right?

Unfortunately, when there is profit to be made, ethics become secondary.

Despite having taken every opportunity from their victims, the killers are repeatedly thrust into the spotlight, often taking precedence over those who died. And while forensic psychology is a burgeoning field worthy of note, the lack of emphasis on the victims erases them from their own story. Everyone knows Ted Bundy and how he lured women to their deaths, but few can name even one of the people he murdered.

Attempts have been made to bridge this critical divide (the book “Bright Young Women” by Jessica Knoll, for instance, which focuses on Bundy’s victims), but it is difficult to capture the rapidly shifting attention of the growing audience. By the time one killer is caught and tried, another is ready to take their place. This constant cycle of new tragedies does not just exhaust public empathy; it fundamentally weakens it, no matter a viewer’s initial reason for watching. Luridity breeds apathy. Dismemberment becomes tame, almost boring—after all, what interest is dismemberment compared to Ed Gein’s death masks? To his shrunken heads and lampshades sewn from flesh?

If the crime becomes too heavy for the audience, however, they can step away from it. The same cannot be said for the families.

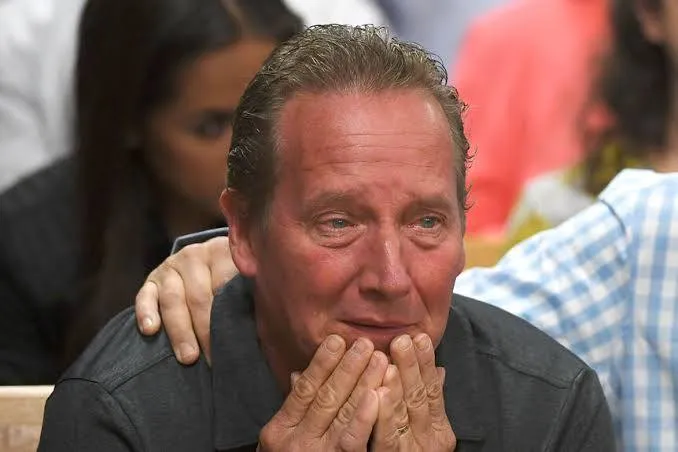

Information about their loved one’s death—and all of the indulgent speculation surrounding it—is not only available to the families but relentlessly shown to them. Their grief becomes something living, bleeding, for the public to dissect. The vivisection becomes the subject of threads aplenty. If a mother did not cry loudly enough at her daughter’s wake, she is viewed just as badly as the killer, and if she cries too loudly, then she has to be putting on a show for the hundreds of cameras.

In many cases, family members are outright harassed. Frank Rzucek—father of then-pregnant Shannan Watts, and grandfather to Bella and Celeste Watts—reports being “trolled” online after his son-in-law murdered all three:

“For the past 11 months, piled on top of pain and the grieving of this devastating loss, our family has been subject to horrible, cruel abuse, outright bullying, on a daily basis … I don’t want to draw more attention to the viral material that has been posted online, but I will say that our family, including Shanann and her children, our grandchildren, have been ridiculed, demeaned, slandered, mocked in the most vicious ways you can imagine.”

There are hundreds of experiences exactly like Rzucek’s, all of which are ignored by the very companies that push these stories. To admit the wrongdoing would be to admit their hand in it. They created the beast and pushed it into the ring, but taking action against it, no matter how passive, would cut into their profits.

However, there are ethical ways to consume true crime content. Certain podcasts, such as “Morbid”, push the victim’s stories in addition to the killer’s and advertise any ongoing fundraisers related to that week’s case. The aforementioned book “Bright Young Women” is well-researched and well-written.

But listening to crime content actively, not passively, does the most good of all. Fact-check content before posting online. Avoid disrespectful, speculative forums, and advocate for the victims whenever possible. Send the message that each crime is more than a commodity—it is a grief that will forever cut into the community.